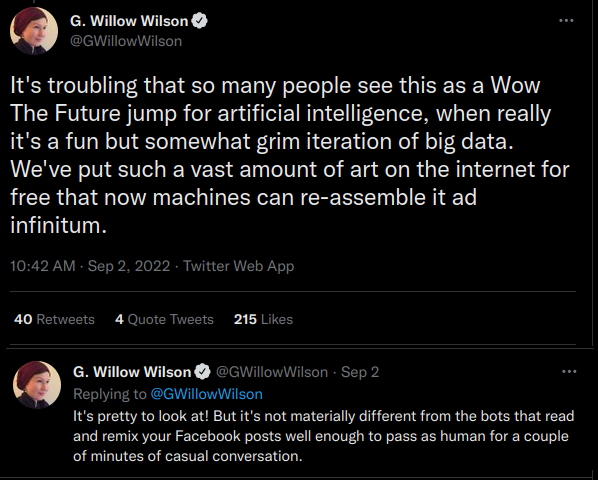

Today I saw a tweet!!! That's a nightmare in itself, but unfortunately I want to discuss the ideas contained within that tweet in order to complain about them.

G. Willow Wilson is an SFF author, and like anyone else on twitter, she has the right to be pessimistic about technology. However, I find this particular variety of technopessimism to be so widespread in contemporary SFF that the resultant discourse can only be described as intellectual laziness.

You've heard of AI art. Everyone has by now. The New York Times wrote about it. Hundreds of thousands of people have used tools like DALL-E mini -- excuse me: "Craiyon, formerly DALL-E mini" -- to create pictures that range from uncannily beautiful to predictably gross.

And now we come to Wilson's core contention: those people aren't "creating" anything. The machine is creating the art, and it's making it based on a dataset of millions (billions? IDK, I build websites, I don't lie to investors about how AI is totally real) of real people's art.

Side note: it's also making these pictures out of thousands of real people's code. A lot goes into these things. Today however we are discussing the art side of AI, because programmers made our bed and if NFTs are any indication, we will die before we stop shitting in it.

Pessimism about technology and its corporate applications suffuses mainstream SFF. Martha Wells' award-winning Murderbot series has as its antagonist the superstructure of corporate-controlled space, along with a few extra-bad corporations. Cyberpunk as a genre overwhelmingly portrays its dystopian future as one determined by capitalism. If you have even passing genre familiarity, then you know the tropes: oh no, BigCo gave me this leg and BigCo can take it away; oh no, I'm mining on an asteroid and I owe money to the company store; oh yeah, I fell in with anarchists and now we're taking over the generation ship, etc. This is a very rich vein to mine in fiction because corporations are awful and capitalism is bad. But there seems to be an interesting shift in how SFF authors view their own art and its relationship to corporate hegemony. Underlying modern SFF is a persistent technopessimism that sees these bleak futures as not just likely but inevitable. The future, they suggest, will be much like the present, but worse, in predictable and consistent ways.

I find this rhetoric tiresome. It's understandable coming from reporters, whose vocation demands they truthfully describe our present. SFF authors are theoretically in the business of imagination. Wilson is very fearful of a world with AI-generated "art"; she explicitly says in replies that she thinks AI-art will foreclose on the future of human involvement in the visual medium. This is a very curious position for an SFF author to take, in my opinion. I can see many bleak futures where AI-art is used to harm people. The most obvious future, of course, is military: the same technology that powers AI-art can be used to recognize humans even when they significantly change their visual presentation. But there are other dank possibilities as well. Humans hunger for creativity; we have created art for the entirety of our existence. What's stopping a corporation from using this tech to generate fakes of a new artist's work for sale as prints, handbags, and so on? What's stopping a corporation from using this tech for product design, edging out indie designers entirely? Theoretically the answer would be "copyright law", but copyright law is lagging behind technology, and of course copyright law primarily exists to benefit corporations. That lag may soon be very obviously by design.

Ideologically, there is nothing wrong with pessimism. It can be a bracing tonic to the treacly optimism of children's stories and mainstream pop culture. But pessimism, like optimism, can facilitate laziness by lending a veneer of legitimacy to otherwise poorly thought out arguments. In this case, I would reiterate: humans hunger for creativity. We have been creating visual art literally for as long as we have been human. We've also been imitating each other's art for a very long time, and historically the result of hollow mimesis has been time-based selection: many bad works of art are forgotten; some contemporaneous popular art doesn't stand the test of time; some art which was obscure during its creator's life becomes timeless a decade or a century later.

We hunger both for originality and skillful iterations on techniques or themes. We hunger for expression, for understanding, for enlightenment. If you are in fact an artist, the idea that art is important to humanity is pretty basic stuff. If you want to argue that a computer program will erase all of that, render it redundant in the face of computer-generated slop1, then I'm going to need you to show your work.

This pearl-clutching is also very funny to me because it is itself an iteration on a very familiar theme. Both I and Wilson are old enough to recall endless debate over the general concept of digital art: its supposed inferiority to physical mediums, its ubiquity and sameness, its tendency to be drawn by anime-obsessed teens who have learned to draw balloon titties but not faces, etc. I recall many people arguing very earnestly that the existence of the Wacom tablet foretold the fall of physical paintings. This has not yet come to pass.

Writers should be students of human nature. SFF writers should be students of human nature specifically as it relates to human systems and history. You can look at AI-generated pictures, think "yikes", and do some tweets about it. But I must request that you at least use your brain to think of more creative pessimistic scenarios. Craiyon, formerly DALL-E mini, is not going to end human-created visual art. The end of visual art will come with the end of humanity and not a moment sooner. I'd like to say the same is true of storytelling, but maybe not if you people keep being so dumb about it.

1 A trendy term. But accurate.